“[T]o write is to struggle and resist; to write is to become; to write is to draw a map: ‘[We are cartographers.’”]

Our aim is to live as and with the Nomadic Detective Agency-Assemblage (NDA). This is a multiplicity, a decentred, and rhizomatic, collective post-human organism that researches possible creative futures. They take their starting points, or lines of flight, from the works of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari (D&G) and especially their jointly constructed book A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. We set the NDA-A off on their adventure by asking them to look at the concept of becoming nomadically educated as a possible way of navigating their journey. The NDA is a vehicle that in its multiplicity will help explore the complexities of a post-human age and how education might be affected.

+

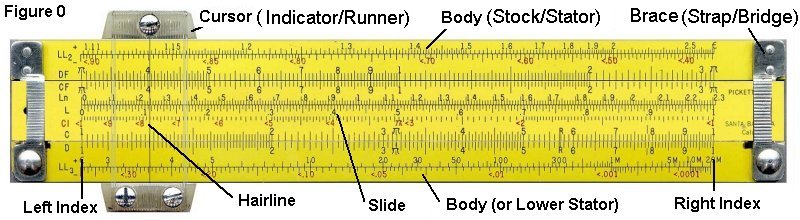

+Rulers: A critical Fabulation

‘The ruler’s rule cut the world into parcels: taxable, ownable, tradable.’

There was once a land measured by breath. A handspan meant the reach of a child’s curiosity, and a cubit the patience of an old woman spinning thread at dusk. Fields were counted in footsteps, rainfalls in remembered songs, and the slow widening of the river marked time. Nothing was exact, yet nothing was wrong.

Then the Rulers arrived.

They came carrying metal rods engraved with certainty. They said the land must be known, measured, numbered, converted. Feet became the measure of the earth. The body was replaced by a foreign limb. The villagers were told their old ways were imprecise, their measures unreliable. So the bamboo rods, still warm from the hands that made them, were cast aside for cold iron scales.

A new kind of ruler stood at the borders of every field, their shadows long and squared. They measured not by need or season but by decree. The harvest became data, the house a value, the body a coordinate on a map. The ruler’s rule cut the world into parcels: taxable, ownable, tradable.

Yet something lingered beneath the numbered gridlines. In the spaces between the inches, the old measures whispered. An ancestor still weighed spices by palmfuls, a farmer still read rainfall by the sound of the roof. These gestures refused conversion. They were quiet insurrections against the imperial calculus.

When independence came, the people were told that now they could measure themselves anew. The rulers would be replaced with meters, universal, rational, liberated from empire. But the ghosts of inches and yards did not vanish. The new rule was still a rule, another promise of precision dressed as freedom.

One day, a child, whose fingers had never held a wooden rod or traced the etched metal of a yardstick, asked: “Who decides how long a meter is?” No one answered. The Rulers had left their tools, but not their logic.

In the dark drawers of old offices, the rulers still lie in rows, their edges stained with fingerprints. They remember the empire that once measured the world into obedience. They gleam faintly, like relics of a faith that mistook control for knowledge.

And somewhere, far from rulers and rules, a hand measures by the memory of touch, an unruled act that cannot be standardised.

From the ruler’s archive

Archival Fragment: Order No. 27, Surveyor-General’s Office

Notice:

By order of their Majesty’s Crown, all units of length, area, and weight in District B will henceforth be reckoned by Imperial standard.

The customary bamboo rods, finger-widths, and seed-weights are declared obsolete.

All subjects must submit lands and stores to proper survey, under penalty of law.

By order of the , Surveyor-General

Diary Entry: Saraswati, Fieldworker (1881)

Today the ruler-men came in boots and blue coats. Their rods gleamed sharper than the sickles. They lined up our fields like counting soldiers.

We whispered the bamboo bends to fit the land. “Why must we cut our fields to match their rod?”

The measure does not fit our crop. Where our hand measure is full of rain, theirs is always dry.

The Ruler

They stand at the edge of the field. Their instrument is impartial, they believe. The world must become quantifiable, converted into tables they will send by ship across the charted water. In their mind, certainty is civilization, and measurement is mastery. Every disputed thumb, every uncounted grain, is chaos to be conquered.

They do not see the child skipping stones across the river, counting in a language untranslatable to the Imperial inch.

Archive Fragment: Petition from the Potters’ Guild (1892)

We, whose ancestors shaped clay by the span of their hands and sold by the weight of river-stone, protest that the new rulers unmake our market and unsettle our worth.

Our craft runs by memory and feel, not yardstick.

We ask: what ruler measures the warmth of a fired bowl, or the taste of a communal feast?

An echo from 1972, one year of Metric Reform)

I tell the story of a dynasty of rulers: one that pressed its weight upon us in inches, another that promised liberation by centimeters.

But every ruler, is still a rule. When you measure, ask whose knowledge counts, whose body is honored, whose world is cut away.

Fragment: The Ruler’s Dream (A Fable)

In his final years, the old ruler dreams of infinite rods, stretching through every land, never bending, never breaking. But as they dream, the rods begin to sprout leaves, singing in bamboo voices. They measure not land but longing, not resources but relationships. They awaken, clutching a wooden piece, struggling to recall what he ruled, and what slipped through his grasp.

Postscript: Whisper

In the market under the banyan tree, a trader sells salt by the pinch. The Rulers no longer watch, but the measure lingers. Their customers know: the pinch is generous, honest, and unruled, not for counting, but for living.

Are we there yet?

Listening to the Stones of Croydon

‘“Think of their age,” Little Bear marvels, the primordial history of the rock and the hoodoos at Writing-on-Stone self-evident. “The stuff they must know!” Yet the “teaching rocks” are somewhat careful about sharing their counsel. When I first visited Writing-on-Stone as a young man in the 1970s, I sensed there was a whole lot going on here that I could not get my head around. “Like a stranger, they will not sit down and tell you everything immediately,” Little Bear says. “Only when the rocks begin to know you will they tell you their story.”'(Little Bear – Listening to Stones – https://scienceandnonduality.com/article/listening-to-stones/)

The Nomadic Detective Agency loves Ursual K. Le Guin… ‘Can we in fact know it? Can we ever understand it?

‘It will be immensely difficult. That is clear. But we should not despair. Remember that so late as the mid-twentieth century, most scientists, and many artists, did not believe that Dolphin would ever be comprehensible to the human brain—or worth comprehending! Let another century pass, and we may seem equally laughable. “Do you realise,” the phytolinguist will say to the aesthetic critic, “that they couldn’t even read Eggplant?” And they will smile at our ignorance, as they pick up their rucksacks and hike on up to read the newly deciphered lyrics of the lichen on the north face of Pike’s Peak.

And with them, or after them, may there not come that even bolder adventurer—the first geolinguist, who, ignoring the delicate, transient lyrics of the lichen, will read beneath it the still less communicative, still more passive, wholly atemporal, cold, volcanic poetry of the rocks: each one a word spoken, how long ago, by the earth itself, in the immense solitude, the immenser community, of space.’ (Ursula K. Le Guin, from The Author of the Acacia Seeds. And Other Extracts from the Journal of the Association of Therolinguistics)

We entangle ourselves with the work of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, jointly authored and by themselves alone, and especially their 1980 book A Thousand Plateaus.

Yes, all becomings are molecular: the animal, flower, or stone one becomes are molecular collectivities, haecceities, not molar subjects, objects, or form that we know from the outside and recognize from experience, through science, or by habit. If this is true, then we must say the same of things human:… (A Thousand Plateaus: p.275 – from plateau – 10. 1730: Becoming-Intense,

Becoming-Animal, Becoming-Imperceptible) https://files.libcom.org/files/A%20Thousand%20Plateaus.pdf

The T factor, the territorializing factor, must be sought

elsewhere: precisely in the becoming-expressive of rhythm or melody, in

other words, in the emergence or proper qualities (color, odor, sound,

silhouette…). Can this becoming, this emergence, be called Art? That would make the

territory a result of art. The artist: the first person to set out a boundary

stone, or to make a mark.(Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari – A Thousand Plateaus: p.3165 – from plateau – 11. 1837: Of the Refrain) https://files.libcom.org/files/A%20Thousand%20Plateaus.pdf

A Speculative Critical Fabulation: A Refrain of the Nomadic Detective Agency

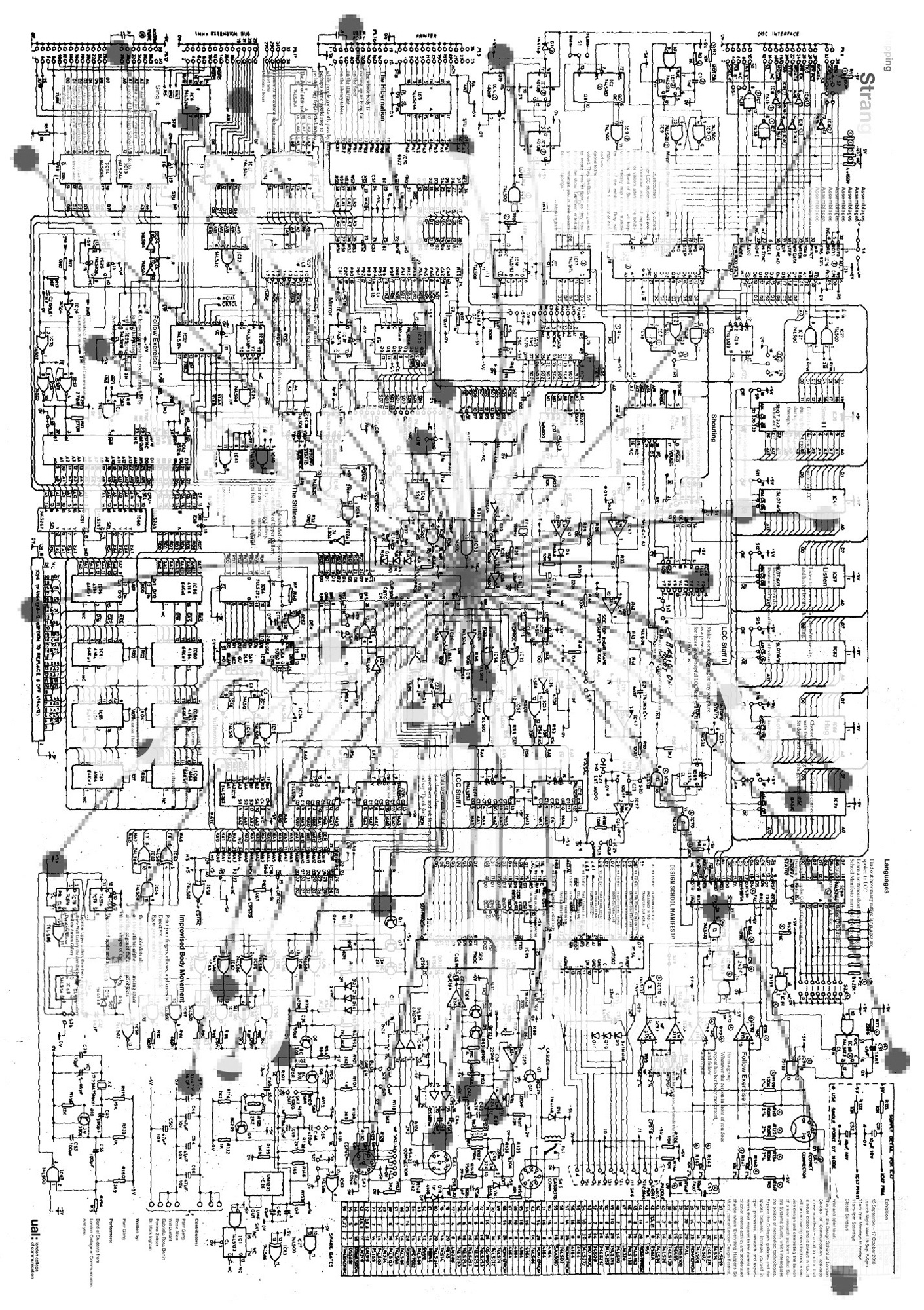

The Nomadic Detective Agency (NDA) begins as a whisper, a refrain rippling through abandoned studios, classrooms, fragmented Zoom calls, and dense forests of forgotten syllabi. “We are cartographers,” we declare, tracing lines of flight across landscapes that no longer hold the hierarchies of centre and margin. Our maps do not delineate borders but reveal intensities, intersections, and flows. They are maps of becoming and are smudgy.

The NDA itself is a paradox: a body without organs, a collective without hierarchy, a machine of thought and action with neither driver nor destination. It assembles itself from fragments, a discarded lathe, telephone, laptop, chalkboard, the hum of servers hosting open-source archives, the laughter of children learning under a tree, the silence of algorithms training themselves in the dark. It does not solve mysteries but becomes them, dissolving the false binaries of question and answer, art and audience, teacher and student, human and machine.

Chapter One: An Inquiry

The NDA receives a case from the ruins of an old university. The question, scrawled on an aging wall, reads: What does it mean to learn in a world where knowledge is everywhere and nowhere? The NDA begins its investigation by tracing the multiplicities embedded in this question.

Its first agent, a collective of artists and coders, follows the line of flight of becoming-nomadic. They wander through the digital deserts of MOOC platforms, where education is reduced to modules, quizzes, and completion badges. Here, they plant seeds of detournement: glitch art courses that destabilize the logic of commodified knowledge. The courses unfold rhizomatically, each click revealing unexpected connections to poetry, quantum physics, and fungi networks.

The second agent, a swarm of AI entities and community elders, follows the refrain of becoming-post-human. They engage in transversal dialogues, hosting interspecies symposia where humans, machines, and ecosystems co-learn. From these encounters emerges a pedagogy of care: a curriculum of listening, attunement, and mutual adaptation.

Chapter Two: SOME Cartographies

The NDA’s maps begin to take shape (they are far from tracings now) and they are not maps as we know them. They are assemblages of scrathes: digital breadcrumbs, oral histories, tags, and mycelial paths. Each map is a multiplicity, a network of potentialities rather than a fixed representation of space.

One map, made of sound, charts the echoes of learning across time. It records the chants of medieval scholars in cloisters,temples, social clubs, and the buzz of public libraries in the 20th century, and the hum of neural networks learning to recognise faces. Another map, tactile and moss-covered, reveals the textures of learning environments: the cold steel of factory classrooms, the warm soil of garden schools, the virtual smoothness of digital forums.

These maps refuse to privilege any one way of knowing. They are cartographies of connection, charting the transversal paths that link disciplines, species, and times.

Chapter Three: A Refrain

The NDA’s journey processes not in resolutions but in refrains. We echo

“To write is to struggle and resist; to write is to become; to write is to draw a map.”

Education, the NDA concludes, is not a destination but an ongoing process of becoming. To be educated nomadically is to traverse lines of flight, to embrace the unknowable, and to co-create with the more-than-human. The NDA leaves its maps open-ended, inviting others to join their multiplicity.

The refrain echoes:

“We are cartographers.”

And as it echoes, it transforms. The NDA is not fixed; it is always becoming, always assembling new agents, new maps, new refrains. Their case is never closed because the mystery of education is endless.

A Manifesto: Making Through Thinking: Because Ideas Are Tools, and Thought Is a Craft and Because Rhizomes Grow Thoughtfully and Make as They Grow.

1. This is a call to consciousness.

In the world of creative education and practice, we have heard it a thousand times: thinking through making. It is a powerful phrase, but it is incomplete. It risks framing making as the origin, and thought as its byproduct. We propose a reversal, a loop, a deeper entanglement: making through thinking. This is a call to detangle.

Creative education too often travels in straight lines, from thought to action, from plan to product. Thinking through making has become the mantra, privileging hands over heads, material over thought. But learning, like creativity, is not linear. It is rhizomatic: sprawling, entangled, horizontal. We propose a shift, not backwards or forwards, but outward: making through thinking.

2. Thinking is not passive. Thinking is not a pause between actions. It is an action. It is not what happens before or after the making — it is making itself. To think well is to shape, bend, carve, assemble, and forge. Ideas are matter. Concepts are raw materials. Reflection is resistance. Philosophy is production. Thinking is a form of movement. In a rhizome, nothing is fixed. Thinking is not a still point between actions. It is action. It moves through materials, across disciplines, between people. To think is to graft, stretch, fold, and mutate. Thinking is not a pause. It is a path.

3. We must reclaim intellectual labour as creative labour. Creative subjects are often dismissed as emotional, intuitive, or hands-on. But behind every brushstroke, script, structure, or system is a rigor of thought, a web of inquiry, a constellation of references and decisions. Thinking is the craft that underpins the craft. We must reclaim thinking as doing. The head and the hand are not separate organs of creativity. They pulse together. Every mark carries a question. Every argument has a shape. Intellectual labour is not a backstage process: it is creative practice in motion.

4. The mind is a workshop. To make through thinking is to prototype in the abstract, to construct with hypotheses, to draft with ethics, to fabricate futures using speculation. The studio / worksop / kitchen table extends into the seminar room, the sketchbook into the footnote, the gallery into the glossary. The mind is a mycelium. Thinking is not solitary. It is networked. Ideas are spores. They connect underground, across contexts, through time. Making through thinking is to design without knowing the destination, to build while wandering, to speculate while sensing.

5. Ideas have form. An idea is not a ghostly thing. It has shape, weight, texture. It demands to be honed, refined, sharpened. To think is to handle material, the material of theory, of context, of memory, of critique. This is not preparation. This is not rehearsal. This is making. Ideas are material. They ooze. They resist. They evolve. To think is to shape the immaterial with the same care we give to clay, sound, wood, or light. In the rhizome, ideas are not foundations: they are filaments.

6. Thinking is a collective practice.

Ideas are made in dialogue. They emerge in friction, in translation, in miscommunication. Making through thinking is not a solitary act, it is relational, contingent, political. Thinking is where we make community, challenge norms, reconfigure power. Thinking is collaborative, transversal, alive.

Ideas emerge in the between-spaces: in dialogue, disagreement, distortion. Rhizomatic learning requires us to listen sideways, to co-compose, to be shaped as we shape. Making through thinking is never solitary. It is always situated.

7. Languages as material. Writing, speaking, reading, listening, these are not side acts. They are central to the creative process. When we write, we make. When we read, we make. When we listen, we make. Language is not documentation of thought. It is thought. Languages (human and more-than-human) are a creative ecology. Speaking, reading, annotating, drafting, these are not accessories to creativity. They are the work. Language is a studio. Syntax is a medium. A footnote can be as radical as a painting. Language doesn’t follow art. It grows with it.

8. Education must honour all sides of these loops. We cannot privilege the tactile and diminish the conceptual. We must create space for thought to be seen as a generative act. This means revaluing theory, philosophy, history, criticism, not as academic accessories, but as creative engines. Education can be rhizomatic. If learning is truly creative, it must be non-linear, interdisciplinary, intersubjective. It must allow for cross-pollination, between ideas and actions, texts and textures, thought and form. Thinking is not scaffolding for making: it is its root system.

9. Making through thinking is slow and meandering. It refuses the speed of production for production’s sake. It insists on context, on ethics, on lineage. It seeks resonance over novelty, relation over repetition, depth over decoration. Making through thinking is slow, strange, and speculative. It resists the fast logic of outcomes and deliverables. It seeks resonance, not resolution. It loops and branches. It fails productively. It makes room for mystery, for mess, for multiplicity

10. This is not a rejection of making. It is its expansion. We still make through making. We still learn with our hands. But we reject the false binary between thought and action. We affirm that to think is to make. To make is to think. And when we remember this, our creative practices become fuller, richer, and more radically alive. This is not a binary. It’s a braid. We still think through making. We still make through making. But we must also recognise thinking itself as making and making as a form of thought. Not as a sequence, but as a simultaneity. Not a hierarchy: a rhizome.

Making Through Thinking is not just a shift in language, it’s a shift in value. In attention. In tempo. It is a demand to see the invisible labour that shapes our creative worlds, and to treat thinking not as preparation for art, but as art itself.

Making Through Thinking is not an inversion of a mantra.

It is a recognition of how ideas truly grow, through a messy, entangled, vibrant ecology of thought and action.

To make is to think.

To think is to make.

To learn is to follow the rhizome, and let it grow wherever it dares.